What are the Characteristics of Japan's Aggregate Wage Dynamics?: An Empirical Study on the New Keynesian Wage Phillips Curve for Japan and the US

Ichiro Muto, Kohei Shintani (Bank of Japan)

Research LAB No.14-E-2, December 1, 2014

Keywords:

Wage; Unemployment rate; New Keynesian theory; Phillips curve

JEL Classification:

E24, E31, E32

Contact:

kouhei.shintani@boj.or.jp (Kohei Shintani)

Summary

We present an empirical analysis on the New Keynesian Wage Phillips Curve (NKWPC) as derived by Gali (2011) using data for Japan and the US. NKWPC provides some theoretical insights on the relationship between wage inflation and the unemployment rate. We find that the empirical performance of Japan's NKWPC is generally superior, and that the slope of Japan's NKWPC is still much steeper than that of the US, although it has flattened in recent years. These results suggest that wages are less sticky in Japan. Taking into account the impact of price inflation on wage dynamics, we find that inflation indexation plays a key role in the US, but is less important in Japan. Analysis of recent data indicates that in both countries the role of inflation indexation is smaller than before. This result might be influenced by low and stable inflation over the past few decades.

1. New Keynesian Wage Phillips Curve: characteristics and estimation method

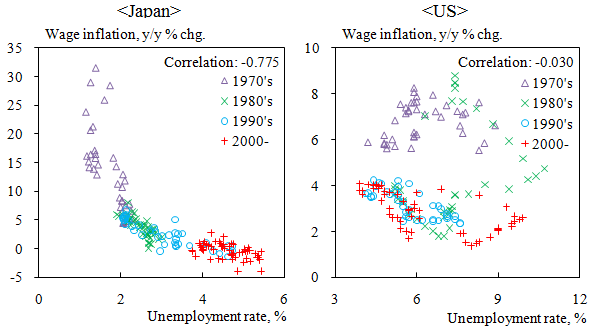

The Phillips curve originally referred to the inverse relationship between wage inflation and the unemployment rate (Phillips (1958)). Figure 1 shows the long-run relationship between wage inflation and the unemployment rate for Japan and the US. There is a stark contrast between the two countries, with the inverse relationship between wage inflation and the unemployment rate remarkably stable in Japan but somewhat tenuous in the US.

Figure 1. Wage inflation and unemployment rate

Sources: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications; Bureau of Labor Statistics.

However, the micro foundations of this Japanese "Phillips curve" have not been adequately addressed in the theoretical literature, making it difficult to gain economic insights into how the relationship between wage inflation and the unemployment rate is determined. By way of contrast, the Phillips curve relating price inflation to unemployment - the so-called New Keynesian Phillips Curve (NKPC) - has solid theoretical foundation and has also been empirically examined in numerous previous studies.

Recently, Gali (2011) derived a New Keynesian Wage Phillips Curve (NKWPC) as a micro-founded structural equation under a sticky wage framework. In the NKWPC framework, the relationship between wage inflation and the unemployment rate is determined by important economic parameters such as wage stickiness and labor supply elasticity. This framework thus provides theoretical insights into the mechanism of wage determination. However, with empirical evidence on the NKWPC so far having been reported only by Gali, more empirical studies using the data of other countries are needed to examine whether the NKWPC can be considered an empirically plausible model. With this goal in mind, we provide empirical evidence on the NKWPC using data for Japan and the US. By comparing the results, we can obtain better understanding on the characteristics of aggregate wage dynamics in these two countries.

There are some previous empirical studies on wage dynamics based on the New Keynesian framework (Sbordone (2006), Koga and Nishizaki (2006)). Following the standard sticky wage framework (Erceg, Henderson, and Levin (2000)), such studies use the "wage markup" (or real wage gap) as a driving force variable for wage dynamics. However, this theoretical wage markup is difficult to observe in actual time series data, and it is still unclear whether the proxies used in previous studies can indeed be considered reasonable approximations. In contrast to these previous studies, Gali and our own analysis use data on the unemployment rate, which is directly observable as a time series, based on Gali's theoretical derivation of a linear relationship between the wage markup and the unemployment rate under certain assumptions for households' labor supply. A key advantage of this approach is the elimination of a conceptual gap between the theoretical framework and the data used in empirical analysis.

In the basic model of the NKWPC, current wage inflation is determined by (i) forward-looking expectations for future wage inflation and (ii) the current unemployment rate. An extended framework allows us to incorporate (iii) wage indexation to price inflation (inflation indexation) into the NKWPC. Inflation indexation in the NKWPC captures the impact of price inflation on wage dynamics, which reflects both explicit and implicit considerations of the inflation rate in wage negotiations between employers and workers. Because the expectations for future wage inflation are unobservable, we estimate the reduced-form of the NKWPC which is derived under the assumption that the unemployment rate follows an autoregressive process. This version of the NKWPC takes a very simple form in which current-period wage inflation is determined by one-period lagged price inflation and the current unemployment rate. Although this specification is similar to the old-fashioned wage Phillips curve, we can interpret the estimation results based on theoretical concepts.

2. Estimation results

We have estimated the reduced-form NKWPC using data for Japan and the US from 1980 to 2013 (Table). For comparison, we have also estimated the reduced form of the basic model of the NKWPC, which excludes the price indexation term. Here we present the estimation results using year-on-year wage inflation data owing to the presence of short-term noise in quarterly wage data, but an estimation using quarter-on-quarter data can be found in Muto and Shintani (2014) [PDF 2,335KB].

Table. Estimation results of the reduced-form NKWPC

| Basic NKWPC | NKWPC with inflation indexation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | US | Japan | US | |

| Unemployment rate | -2.041 | 0.005 | -1.560 | -0.191 |

| (-20.96) | (0.07) | (-11.46) | (-4.49) | |

| One-period lagged inflation rate | -- | -- | 0.396 | 0.529 |

| (4.72) | (17.56) | |||

| const. | 0.089 | 0.034 | 0.069 | 0.028 |

| (24.88) | (6.78) | (12.48) | (10.04) | |

| Adj-R2 | 0.767 | -0.008 | 0.800 | 0.697 |

(Note) Sample period is 1980Q1-2013Q2 in every case. t-values in parentheses.

Year-on-year wage inflation data is used. Year-on-year change of CPI (all items less fresh food) is used as inflation rate for Japan, and CPI (all items less food and energy) is for the US.

Our main findings can be summarized as follows.

- (1) In Japan, the unemployment rate has significant explanatory power for variations in wage inflation, irrespective of whether or not wages are indexed to price inflation. In the US, however, the unemployment rate is statistically significant only when we allow for inflation indexation. Moreover, even if we incorporate inflation indexation, the absolute value of the coefficient on the unemployment rate is significantly smaller in the US. This means that the slope of the wage Phillips curve is steeper in Japan than in the US.

- (2) In both countries, one-period lagged price inflation has significant explanatory power for wage inflation. However, the improvement in the empirical fit of the NKWPC due to the inclusion of an inflation indexation term is especially large in the US. This indicates that inflation indexation plays a particularly important role in the US.

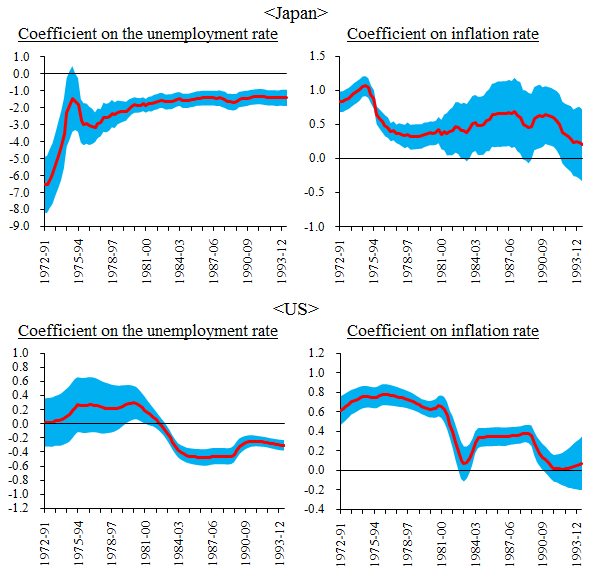

These estimation results are based on time series data for the 1980s onwards. Using the data from 1972 to 2013, our study also looks at possible changes in the relationship between wage inflation, the unemployment rate, and price inflation by carrying out rolling regressions with 20-year rolling windows (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in reduced-form NKWPC coefficients

(Note) Rolling window is 20 years. Shaded area indicates the range of two standard errors.

The results of our rolling regressions can be summarized as follows.

- (1) The absolute value of the coefficient on the unemployment rate has been declining in Japan while becoming statistically significant in the US. However, it is larger for Japan than for the US throughout our entire sample period.

- (2) The coefficient on price inflation has been declining in both countries, and has lost statistical significance in recent years.

3. Interpretations of the estimation results and implications

These estimation results give us some insight into Japan's wage dynamics. First, even though the slope of the NKWPC has been flattening in recent years, it remains much steeper than in the US. The theoretical underpinnings of the NKWPC imply that wages are less sticky in Japan than in the US. This might be related to the fact that adjustment in Japan's labor market typically involves changes to wage levels rather than employment (hiring or firing), reflecting the existence of work-sharing conventions and flexible wage contracts. Although deeper investigation of these aspects is left for future research, our empirical results do at least suggest that tightening of the labor market is more likely to induce faster wage inflation in Japan than in the US.

Second, our full-sample estimation indicates that inflation indexation plays a more important role in the US than in Japan. However, analysis of recent data suggests that inflation indexation is now less important in both countries than before. One possible explanation is that inflation rates in both countries have been lower and more stable over the past few decades. As such, there may be less need to make explicit allowance for fluctuations in the inflation rate during periods when it is low and comparatively stable. Estimation results including data for the high-inflation era of the early 1970s show that the price inflation rate has a large impact on the wage inflation rate, even in Japan. In other words, our analysis suggests that the role of inflation indexation can vary over time depending on the prevailing level and volatility of the price inflation rate.

References

- Erceg, Christopher, Dale Henderson, and Andrew Levin (2000), "Optimal monetary policy with staggered wage and price contracts," Journal of Monetary Economics, 46(2), pp. 281-313.

- Gali, Jordi (2011), "The return of the wage Phillips curve," Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), pp. 436-461.

- Koga, Maiko, and Kenji Nishizaki (2006), "Estimating price and wage Phillips curve: sticky price and wage model [PDF 262KB]," Monetary and Economic Studies (Japanese version), 25(3), pp. 73-106 (in Japanese).

- Muto, Ichiro, and Kohei Shintani, "An Empirical Study on the New Keynesian Wage Phillips Curve: Japan and the US [PDF 2,335KB]," Bank of Japan Working Paper, No. 14-E-4.

- Phillips, A. W. (1958), "The relation between unemployment and the rate of change of money wage rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957," Economica, 25, pp. 283-299.

- Sbordone, Argia (2006), "U.S. wage and price dynamics: a limited-information approach," International Journal of Central Banking, 2(3), pp. 155-191.

Notice

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Japan.