Household Inflation Expectations: The Term Structure and the Anchor Effects of Monetary Policy

Koichiro Kamada, Jouchi Nakajima (Bank of Japan)

Research LAB No.15-E-5, September 30, 2015

Keywords:

Inflation expectations; Term structure; Inflation target; Inflation anchor; Quantitative and qualitative monetary easing

JEL Classification:

E31, E52, E58

Contact:

kouichirou.kamada@boj.or.jp (K. Kamada)

Abstract

The management of inflation expectations is one of the means by which central banks aim to achieve price stability. This is the reason why central bankers are required to have a deep understanding of the dynamics of inflation expectations. Kamada et al. (2015) [PDF 835KB] examined a household survey and found that short-term and long-term inflation expectations behave differently: short-term expectations are easily affected by actual inflation, while long-term expectations are stable and immune to actual price developments. This result indicates that inflation expectations are anchored to a certain level in Japan from the long term point of view. Long-term expectations, however, are changeable and influenced by monetary policy. The price stability target and quantitative and qualitative monetary easing introduced by the Bank of Japan in 2013 are likely to raise and stabilize inflation expectations in Japan.

Introduction

Keynes contrasted short-term and long-term expectations in his General Theory. Short-term expectations were characterized as follows: "[T]he most recent results usually play a predominant part in determining what these expectations are" (Keynes, 1936, p. 51). On the other hand, long-term expectations were described as follows: "[I]t is of the nature of long-term expectations that they cannot be checked at short intervals in the light of realized results" (ibid). However, he did not claim that long-term expectations were invariable: "[Long-term expectations] are liable to sudden revision. Thus the factor of current long-term expectations cannot be even approximately eliminated or replaced by realized results" (ibid).

Keynes's insight gives us an important clue for understanding the nature of household inflation expectations. When prices are rising, households expect inflation to continue for a while. At the same time, they assume that the inflation rate will return to its steady state level in a few years. The important point is that the steady state level of inflation, which is supposed to be reached in the medium to long run, depends on households' understanding of a central bank's monetary policy stance (Bernanke, 2007). In this essay, we examine how long-term and short-term inflation expectations responded to a change in the actual rate of inflation, and investigate to what extent the Bank of Japan's monetary policies have influenced and strengthened the anchor of inflation expectations.

The Term Structure of Inflation Expectations

The Opinion Survey on the General Public's Views and Behavior is a survey conducted by the Bank of Japan (BOJ) since 1993 to monitor households' various economic perceptions, including price developments and monetary policy. The survey asks households three questions about inflation: (i) current inflation perceptions or a realized inflation rate from a year ago, (ii) 1-year inflation expectations or short-term inflation expectations a year from now, and (iii) 5-year inflation expectations or long-term inflation expectations over the next five years per annum. For each of these questions, households are asked a quantitative as well as a qualitative question. We focus on the answers to the quantitative question. In the case of long-term inflation expectations, the question reads "By what percent do you think prices will change per year on average over the next five years?"

Various distortions are included in households' survey responses on inflation expectations. Kamada (2013) examined the micro-data from the survey and pointed out the following four distortions: there are (i) too many integers, (ii) zeros, and (iii) multiples of 5, but (iv) too few negative values. He argues that distortions (ii) and (iv) are both consequences of the downward rigidity of price expectations. He pointed out that the methodology of the survey introduces another distortion. That is, inflation expectations collected by mail tend to be higher than those collected by survey investigators who visit households in person. These distortions should be removed in order to understand the dynamics of inflation expectations correctly and to evaluate the effects of monetary policy on inflation expectations precisely. Kamada et al. (2015) devised such a statistical tool: it enables us to see the underlying distribution of inflation expectations, which would be obtained if there were no distortions in the survey.

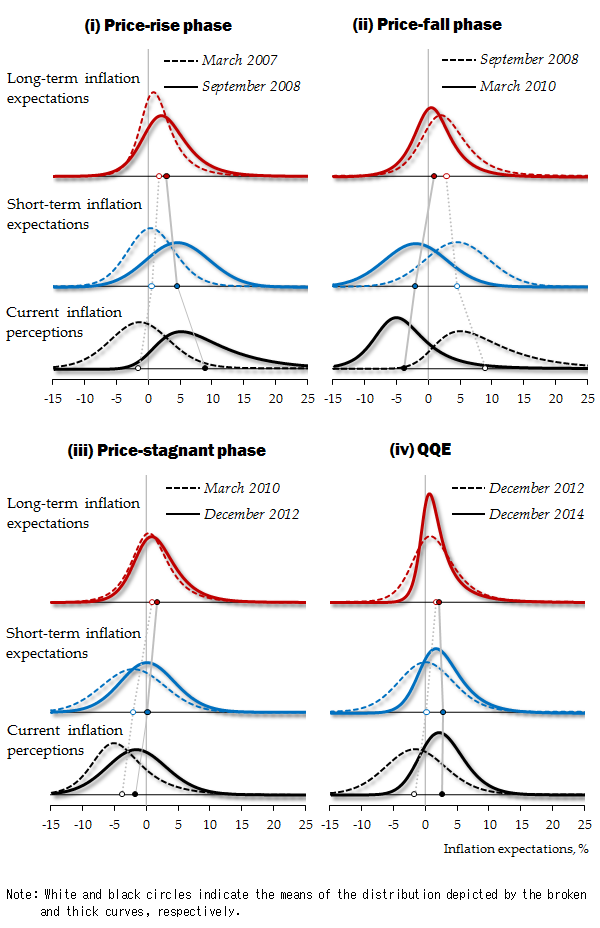

To clarify the dynamic relationship between long-term and short-term expectations, we divide the sample into four subsamples according to the developments of current inflation perceptions. In each panel of Figure 1, the underlying distributions of long-term inflation expectations are placed at the top; those of short-term inflation expectations in the middle; those of current inflation perceptions at the bottom. The underlying distributions drawn by the broken line are obtained from the first round of the survey conducted in each phase, while those drawn by the thick line are constructed from the final round of the survey in the same phase. White and black circles indicate the mean values of the underlying distributions. The lines connecting those circles swing to the right in inflation phases and to the left in deflation phases like a pendulum. That is, the swing of long-term inflation expectations is smaller than that of short-term expectations. Furthermore, the dispersion of long-term inflation expectations is smaller than that of short-term expectations. These findings suggest that from the long term point of view, household inflation expectations have been anchored to a certain level in Japan.

Figure 1: The Term Structure of Inflation Expectations

The Effects of Monetary Policy

The above result indicates that the BOJ's monetary policy has contributed to strengthening, or at least has not ruined, the anchor of inflation expectations as a whole. But it is fair to mention that not all the monetary policies implemented in the past contributed to stabilizing inflation expectations. Kamada et al. (2015) examined individual policies implemented by the BOJ since September 2006 separately and analyzed whether and how those policies influenced the process of formation of households' expectations. They focused on the following two policies that might have influenced households' expectations.

First, the BOJ introduced comprehensive monetary easing in October 2010. As seen in Table 1, the policy succeeded in raising the level of inflation expectations. The mean of long-term inflation expectations shifted up discretely by about one percent point, up to the ceiling rate of 2 percent in the framework of the understanding of medium- to long-term price stability, introduced in 2006 and clarified in 2009 by the BOJ. The rise in short-term expectations was much larger: the mean jumped up by more than 2 percent points from a negative to a positive value. However, no significant changes were observed in other statistics, particularly in the variance.

Second, the BOJ introduced a price stability target in January 2013 and quantitative and qualitative monetary easing in April 2013. As shown in Table 1, the mean of short-term expectations jumped up drastically by about 2 percent points up to the target level of 2 percent. The mean of long-term expectations also rose significantly in a statistical sense, though the rise appeared to be quite small. In addition, as shown by Kamada et al. (2015), inflation expectations, both long-term and short-term, have become less susceptible to actual price movements. Furthermore, the effects of the policy are larger among households who are well aware of the BOJ's objectives than among those who are not. Similar effects were observed when comprehensive monetary easing was introduced.

Table 1: Changes in the Underlying Distribution of Inflation Expectations

| Long-term inflation expectations | Mean (%) | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |||||

| December 2009 | 1.24 | 1.15 | 17.6 | 18.3 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 2.55 | 2.97 | ||||

| October 2010 | 1.15 | 1.76 | *** | 18.3 | 17.1 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 2.97 | 2.67 | |||

| February 2012 | 1.76 | 1.89 | 17.1 | 15.9 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 2.67 | 2.11 | ||||

| January 2013 | 1.89 | 2.08 | * | 15.9 | 13.3 | * | 0.71 | 2.24 | *** | 2.11 | 10.82 | *** |

| Short-term inflation expectations | Mean (%) | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |||||

| December 2009 | -1.05 | -1.19 | 28.9 | 27.3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.18 | ||||

| October 2010 | -1.19 | 0.93 | *** | 27.3 | 28.1 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.09 | |||

| February 2012 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 28.1 | 25.3 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.16 | ||||

| January 2013 | 0.85 | 2.59 | *** | 25.3 | 16.1 | *** | 0.05 | 0.62 | *** | 0.16 | 1.36 | * |

Notes:

- We divide the period from March 2009 to December 2014 into five subsamples with four specified months in the table as separations, and conduct statistical tests to compare the descriptive statistics of adjacent subsamples separated by each month. The null hypothesis of the statistical test is "the mean / variance / skewness / kurtosis is equal between two subsamples."

- In December 2009, the meaning of the understanding of medium- to long-term price stability was clarified. In December 2010, comprehensive monetary easing (CME) was introduced. In February 2012, the price stability goal in the medium to long term was introduced. In January 2013, the price stability target was introduced.

- ***, * indicate significance at the 1% and 10% levels, respectively.

One of the most interesting facts about the 2013 policies is that they changed the shape of the distribution of inflation expectations. First, the variance of inflation expectations, both long term and short term, was reduced significantly. This means that household inflation expectations converged. Second, as pointed out by Nishiguchi et al. (2014), the skewness and kurtosis of inflation expectations, especially of long-term expectations, jumped up immediately after the introduction of the policies. The rise in skewness implies that the convergence occurred as the number of households who expected low inflation rates decreased. The rise in kurtosis suggests that the convergence occurred among households whose expectations were around the average, but not among those whose expectations were extreme. This is a consequence of the fact that inflation expectations of policy-sensitive households, i.e., those who well understand the central bank's objectives, tend to be located around the mean value (see Nishiguchi et al. 2014). In contrast, no impact was observed on the shape of the underlying distribution in the case of comprehensive monetary easing.

The Effectiveness of Inflation Targeting

Since its introduction of the understanding of medium- to long-term price stability in March 2006, the BOJ has strengthened the definition of price stability in steps. That is, the understanding of medium- to long-term price stability was clarified in December 2009; the price stability goal in the medium to long term was introduced in February 2012; and the price stability target was introduced in January 2013. But the 2009 and 2012 policies had no significant impact on inflation expectations. Why not? Conversely, why did the price stability target introduced in 2013 have a significant impact on inflation expectations?

Kamada et al. (2015)'s analysis suggests that announcing a target rate of inflation is not enough for inflation targeting to be effective, and that the policy works only if it is implemented together with some other drastic policies that make the central bank's commitment credible. In the case of the price stability target, it functioned effectively since it was followed immediately by quantitative and qualitative monetary easing. In the case of clarifying the understanding of medium- to long-term price stability, it was not effective until comprehensive monetary easing was introduced later. To enhance policy performance, we should collect empirical facts further, regarding what policy package, including large-scale asset purchases, forward guidance, etc., should be implemented together with inflation targeting.

References

- Bernanke, Ben S. (2007), "Inflation Expectations and Inflation Forecasting (Link to an external website)," speech at the Monetary Economics Workshop of the National Bureau of Economic Research Summer Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts, July 10, 2007.

- Kamada, Koichiro (2013), "Downward Rigidity in Households' Price Expectations: An Analysis Based on the Bank of Japan's 'Opinion Survey on the General Public's Views and Behavior' [PDF 1,906KB]," Bank of Japan Working Paper Series, No. 13-E-15.

- Kamada, Koichiro, Jouchi Nakajima, and Shusaku Nishiguchi (2015), "Are Household Inflation Expectations Anchored in Japan? [PDF 835KB]" Bank of Japan Working Paper Series, No. 15-E-8.

- Keynes, John M. (1936), The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, London: Macmillan.

- Nishiguchi, Shusaku, Jouchi Nakajima, and Kei Imakubo (2014), "Disagreement in Households' Inflation Expectations and Its Evolution [PDF 390KB]," Bank of Japan Review Series, No. 14-E-1.

Notice

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Japan.