Current Discussion on the Legal System regarding "Uncertificated Securities"

Atsuto Suzuki (Bank of Japan)

Research LAB No.15-E-6, November 10, 2015

Keywords:

Book-Entry Transfer Securities; Customer Protection; Legal Theory

JEL Classification:

G21, G24, G33, K22

Contact:

atsuto.suzuki@boj.or.jp

Abstract

Though paper-based securities have been widely used, in order to avoid costs of storage and transportation -- and risks of theft and loss -- associated with the delivery of paper-based securities, recent years have seen development of the legal system in Japan with respect to rights in securities based on electronic records. In tandem with this development, legal theory based on paper-based securities has had to be reviewed and modified. By reference to approaches taken in foreign countries, in Japan it will be important to continue discussing judicial reasoning and legislation regarding rights in securities based on electronic records. This article is based principally on the Reports of Workshops (see References) in which the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies at the Bank of Japan served as the secretariat.

Introduction

Though paper-based securities have been widely used, with increased issuance and circulation, there is now a high level of recognition of the burden created in having to securely and physically deliver a large amount of paper-based securities. In light of this situation, the legal system with regard to rights in securities based on electronic records has developed in recent years, replacing paper-based securities. For example, the Act on Book-Entry of Company Bonds, Shares, etc. created the Book-Entry Transfer System whereby rights in CP, company bonds, Japanese government bonds and shares are managed through records in the book-entry transfer account registry maintained by book-entry transfer institutions and account management institutions.

The development of this legal system has overcome issues such as costs of storage and transportation, as well as risks of theft and loss, associated with the delivery of paper-based securities, and at the same time, legal theory based on paper-based securities has had to be reviewed and modified. For example, in order to assert against third parties that one is the "true owner," it has been thought that one needs to take delivery of paper-based securities. However, in order to assert the same under the electronic records mechanism, it is not clear what is required. Rights in securities based on electronic records are managed in accordance with records held in the registry. However, because a transfer takes effect only when assignor and assignee intend to transfer rights in securities, there may arise a situation in which the true owner cannot be reliably identified based on registry records alone. Thus, for example, when a registered holder who is not the true owner goes bankrupt, there is an issue over whether the true owner can assert torimodoshi-ken against the trustee. Torimodoshi-ken is the right to segregate property from the bankruptcy estate. In order to exercise the right of segregation, it is necessary to have the substantive right (ownership, etc.) underlying the right of segregation.

Customer's right of segregation when securities company goes bankrupt

When a customer sells and/or purchases listed shares, it is common practice to entrust execution of the relevant transactions to a securities company. On the sale of listed shares on a securities exchange, the customer entrusts the sale of said securities and delivers them to a securities company, after which the securities company sells the securities and settles the transactions through a clearing organization. If the securities company goes bankrupt in the meantime, though separate management is required for a securities company, there is a possibility that the listed shares entrusted by the customer will become commingled with the securities company's own assets because the settlement process requires that the listed shares be transferred via the securities company's own account. Similarly, when purchasing listed shares, if the securities company goes bankrupt before the listed shares are delivered to the customer, there is a possibility that the listed shares will become commingled with the securities company's own assets.

In such a case, because the securities remain recorded in the securities company's own book-entry transfer account, there is an issue over whether the customer can assert the right of segregation against the creditors of the securities company. In addition, while the safety net provided by the Japan Investor Protection Fund is in place for customers who cannot reclaim their securities from bankrupt securities companies, not all customers are compensated by the fund. Thus, it is important to discuss the rights of customers under current private laws.

The rights of customers in securities entrusted for sale

Traditional view under the paper-based securities mechanism

Under the paper-based securities mechanism, when securities company X has been entrusted with the sale of securities by customer A, and goes bankrupt after entering into a sale and purchase agreement with securities company Y and receiving the securities from A but before transferring them to Y, A has been thought to benefit from the right of segregation. In other words, it has been conceivable that a securities company, which engages in the business of selling and purchasing securities based on customer instructions, constitutes a typical commission agent (toiya), and that because a customer grants only the right to dispose of securities to a securities company, the customer is entitled to segregation in the event of the securities company's bankruptcy.

The right of segregation for book-entry transfer securities entrusted for sale

In contrast, under the electronic records mechanism, a customer's delivery of book-entry transfer securities to a securities company is carried out by a transfer from the securities company's customer account to the securities company's own account. Under this mechanism, there is an issue over whether A (in the example given above) benefits from the right of segregation if the securities remain recorded in X's own account at the time of the latter's bankruptcy.

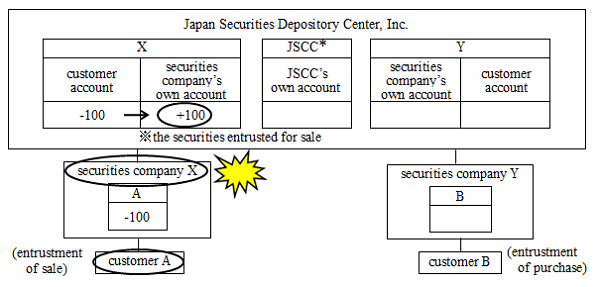

(Figure 1) Settlement Process of Sale of Securities (securities company X goes bankrupt)

- Japan Securities Clearing Corporation

(Source) Workshop on "Holding, Transferring and Pledging Assets in Financial Transactions" (2013)

For a customer to exercise the right of segregation, it is necessary to have the substantive right underlying the right of segregation. There are two competing views on this issue:

Under the first view, even though the securities are recorded in the securities company's own account, because the customer's transfer of securities to the securities company carries with it only the right to dispose of said securities and there is no intention to transfer them to the securities company, no such transfer takes effect. Therefore, the rights attached to book-entry transfer securities are not transferred, and the customer has the substantive right underlying the right of segregation in bankruptcy proceedings;

Under the second view, in line with the reality of the settlement process whereby book-entry transfer securities are sold and/or purchased via a securities company's own account, it is implied that a customer who entrusts the sale and/or purchase of securities to the securities company agrees to transfer the securities via the consignee securities company. Hence, the rights attached to securities recorded in the securities company's own account belong to the securities company, and the customer does not have the substantive right underlying the right of segregation in bankruptcy proceedings.

The rights of customers in securities entrusted for purchase

Traditional view under the paper-based securities mechanism

Under the paper-based securities mechanism, when securities company Y has been entrusted with the purchase of securities by customer B and goes bankrupt after entering into a sale and purchase agreement with securities company X and receiving the securities from X, but before delivering them to B, the securities which should have been delivered to B remain in bankrupt Y. In this case, in terms of the relationship between commission agent and consignor, the consignor (customer B) is attributed the rights attached to securities the agent (securities company Y) was originally commissioned to deliver to the consignor. However, dispute has arisen over whether the consignor can assert the right of segregation against the creditors of the commission agent. In this regard, a Supreme Court judgment (July 11, 1968; 22 Minsyu 7 [1462]) has confirmed the customer's right of segregation, holding that it is the consignor that has the substantive rights to assets the commission agent acquires, and that creditors of the commission agent should not expect all assets registered under the name of the commission agent to become collateral for their claims. This judgment has been strongly criticized for lacking theoretical reasoning and being based solely on balancing competing interests. However, there is much support for the conclusion itself.

The right of segregation for book-entry transfer securities entrusted for purchase

An issue that arises from the above discussion is whether under the electronic records mechanism -- the Book-Entry Transfer System -- B (in the foregoing example) benefits from the right of segregation if the securities are recorded in Y's own account at the time of the latter's bankruptcy.

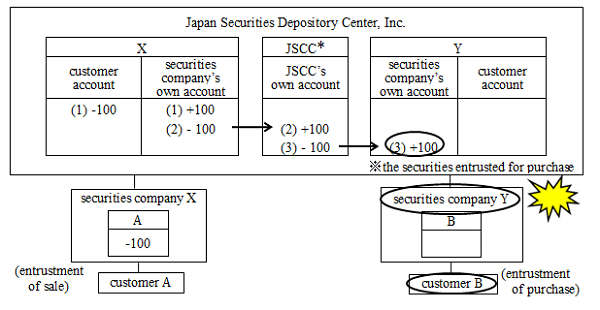

(Figure 2) Settlement Process of Purchase of Securities (securities company Y goes bankrupt)

- Japan Securities Clearing Corporation

(Source) Workshop on "Holding, Transferring and Pledging Assets in Financial Transactions" (2013)

As mentioned before, for a customer to exercise the right of segregation, it is necessary to have the substantive right underlying the right of segregation. It is stipulated that transfers of book-entry transfer securities shall not take effect unless the securities being transferred are recorded in the transferee's own account. Thus, as long as the securities remain recorded in the securities company's own account, the customer does not seem to benefit from the right of segregation. In addition, in line with the reality of the settlement process, it is implied that the securities are first transferred to a securities company. Securities the securities company has been instructed to purchase and of which it has already taken delivery belong to the securities company, and the customer does not have the right to have them segregated in the event of the securities company's bankruptcy.

Thus, it is theoretically difficult to establish customer protection. In this sense, the 1968 judgment, which has been criticized for its lack of theoretical reasoning but confirms the customer's right of segregation, becomes more important under the electronic records mechanism.

Proposals for legislation in Japan

It is not absolutely clear whether the rights of a customer to sell and/or purchase securities through a securities company are protected at the time of the latter's bankruptcy. Hence, one potential option is to make new legislation granting customers the right of segregation in respect of securities entrusted for sale or purchase. Drawing on examples from foreign countries, this article proposes two directions in which legislation in Japan might be oriented.

First, legislation prescribing that securities rights shall be transferred directly from one customer to another without being held temporarily by a securities company should be considered. This would reflect the treatment in the United Kingdom, the United States and France. The transfer of rights (ownership, etc.) to assets in which a commission agent intervenes would be constructed as a direct transfer from the seller to the consignor, and the assets purchased by the consignor would not be deemed to belong to the commission agent.

Next, it is conceivable to introduce legislation prescribing that when a securities company goes bankrupt, its customers shall be entitled to reclaim securities entrusted to the securities company for sale or purchase. This would reflect the treatment adopted in the United States and Germany. Specifically, it is possible to introduce legislation prescribing that if a securities company goes bankrupt after being entrusted with the sale of securities and taking delivery of the same from the customer, but prior to execution of the sale, the customer shall be entitled to reclaim the securities. Similarly, if a securities company goes bankrupt after being entrusted with the purchase of securities by a customer and taking delivery of the securities from the other party (the seller), but prior to delivery of the same to the customer, as long as the customer has paid the purchase price, the customer shall be entitled to reclaim the securities. However, because such legislation would stipulate a treatment that differs from the treatment of substantive rights, such special treatment would be, from the viewpoint of public notice, limited to a genuinely necessary case. The 1968 judgment and the discussions thereof stressed the fact that it was commonly known that securities companies were entrusted with the sale and/or purchase of securities by customers in the ordinary course of their business. Therefore, such special treatment should be limited to securities held by securities companies undertaking brokerage business.

(Figure 3) Examples in Foreign Countries

| Japan | USA | UK | France | Germany | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right of Segregation | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Legal Treatment | Rights Transfer System in Brokerage Business | Securities Companies Temporarily Hold Rights. | Rights are Directly Transferred to Customers. | Rights are Directly Transferred to Customers. | Rights are Directly Transferred to Customers. | Securities Companies Temporarily Hold Rights. (With Agreement, however, Rights can be Directly Transferred to Customers.) |

| Special Priority* | No, as for rights based on electronic record (Yes, as for paper-based securities) |

Yes (Securities Investment Protection Act (1970)) |

No | No | Yes (Gesetz über die Verwahrung und Anschaffung von Wertpapieren (1937)) |

|

- Special Priority to a Customer at the Time of the Bankruptcy of a Securities Company

(Source) Workshop on "Holding, Transferring and Pledging Assets in Financial Transactions" (2013)

Conclusion

With development of the legal system based on electronic records, it has been necessary to review and modify legal theory based on paper-based securities.

In the past, when the U.S. Uniform Commercial Code provisions related to electronic records was first referred to in Japan, there was a debate over how to translate the term "uncertificated securities." Introduction or adaption of a new legal system necessitates the examination of many issues.

Depending on the characteristics of rights based on electronic records and the development of financial business practices, in Japan it will be important to continue discussing judicial reasoning and legislation regarding rights in securities based on electronic records.

References

- Report of Workshops on "Holding, Transferring and Pledging Assets in Financial Transactions," Kin'yu Kenkyu (Monetary and Economic Studies), 32 (4), Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies, Bank of Japan, 2013, pp. 25-104 (in Japanese).

- Report of Workshops on "Dematerialized Securities and Electronically Recorded Monetary Claims," Kin'yu Kenkyu (Monetary and Economic Studies), 34 (3), Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies, Bank of Japan, 2015, pp. 1-66 (in Japanese).

Notice

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Japan.